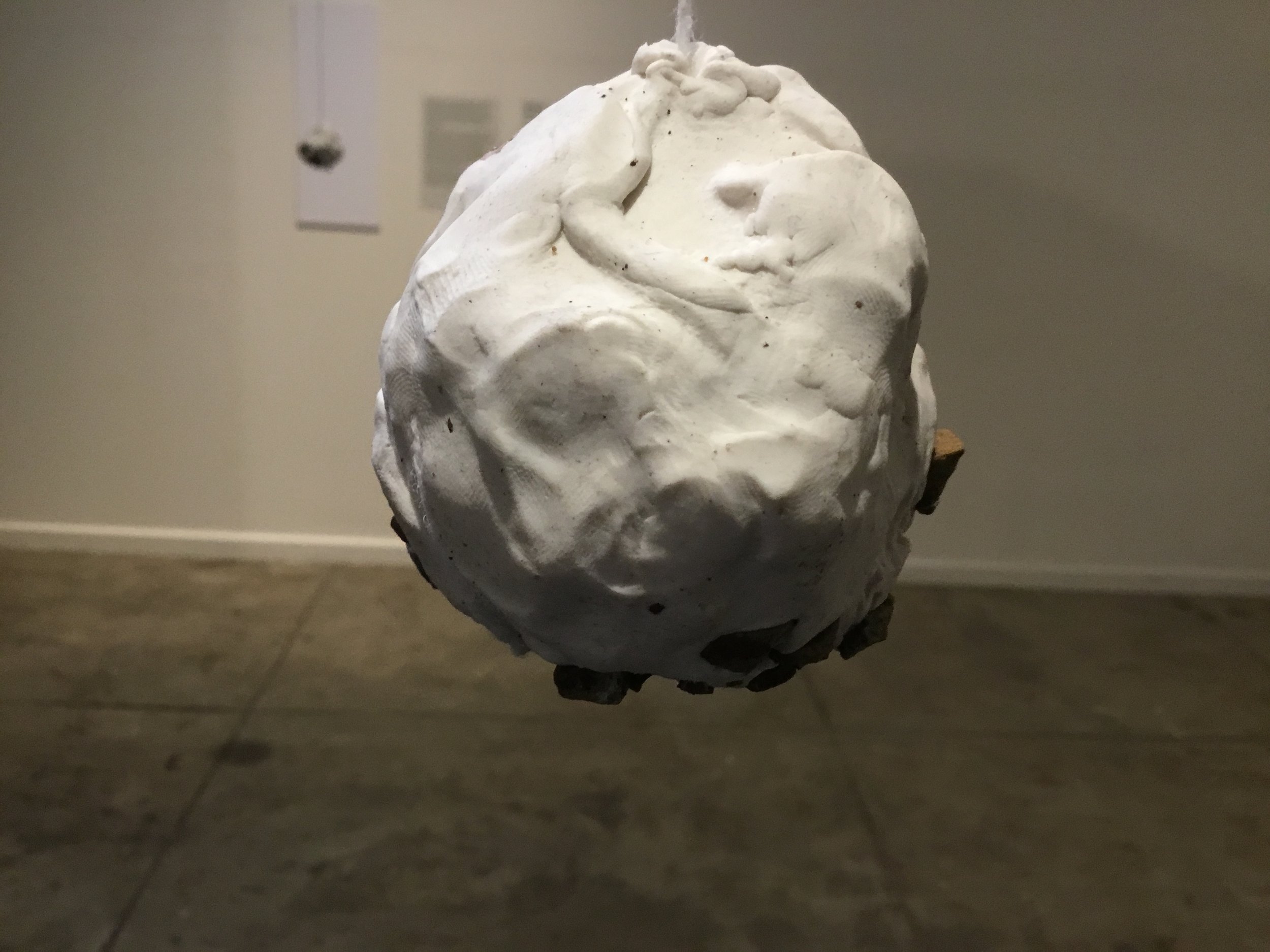

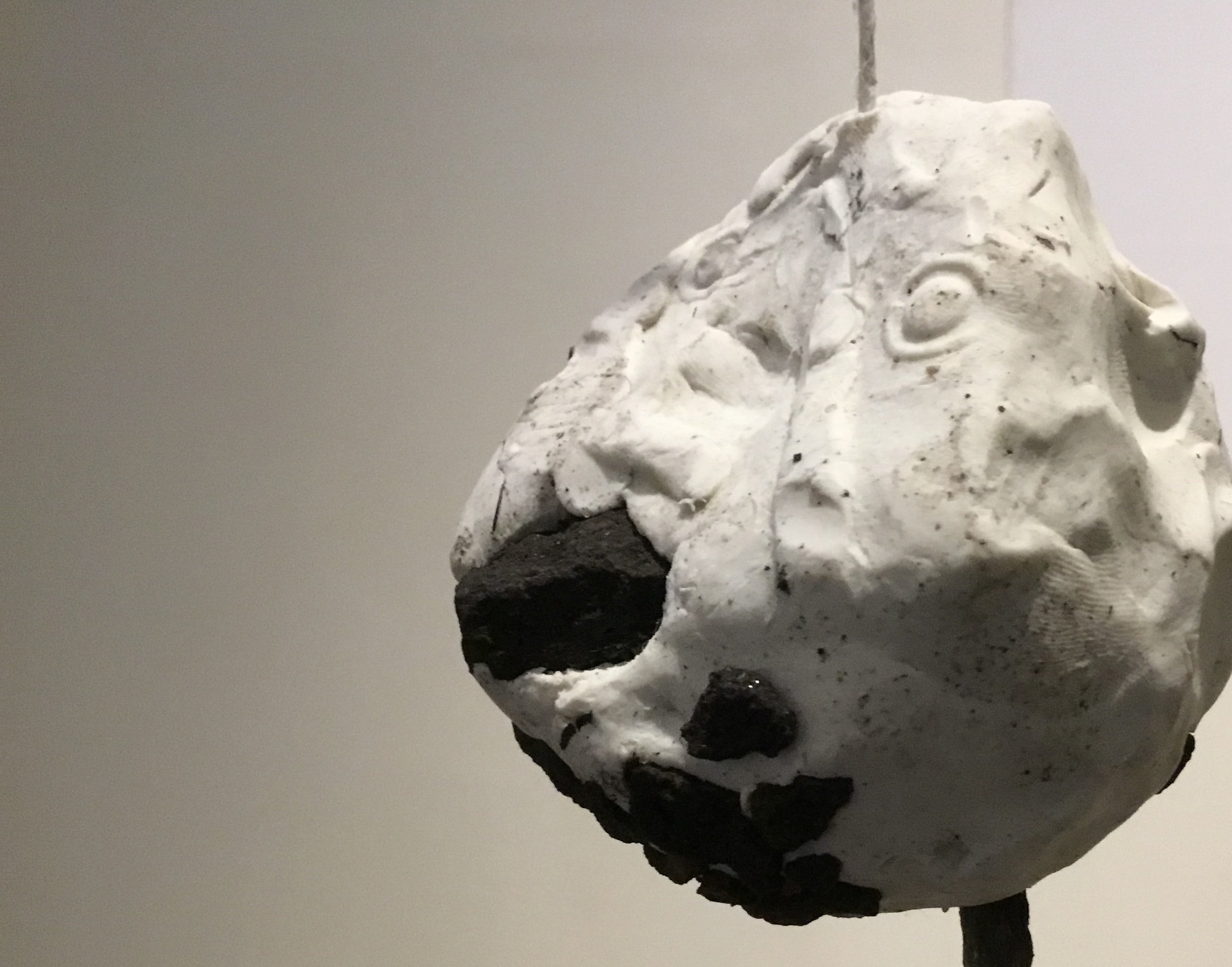

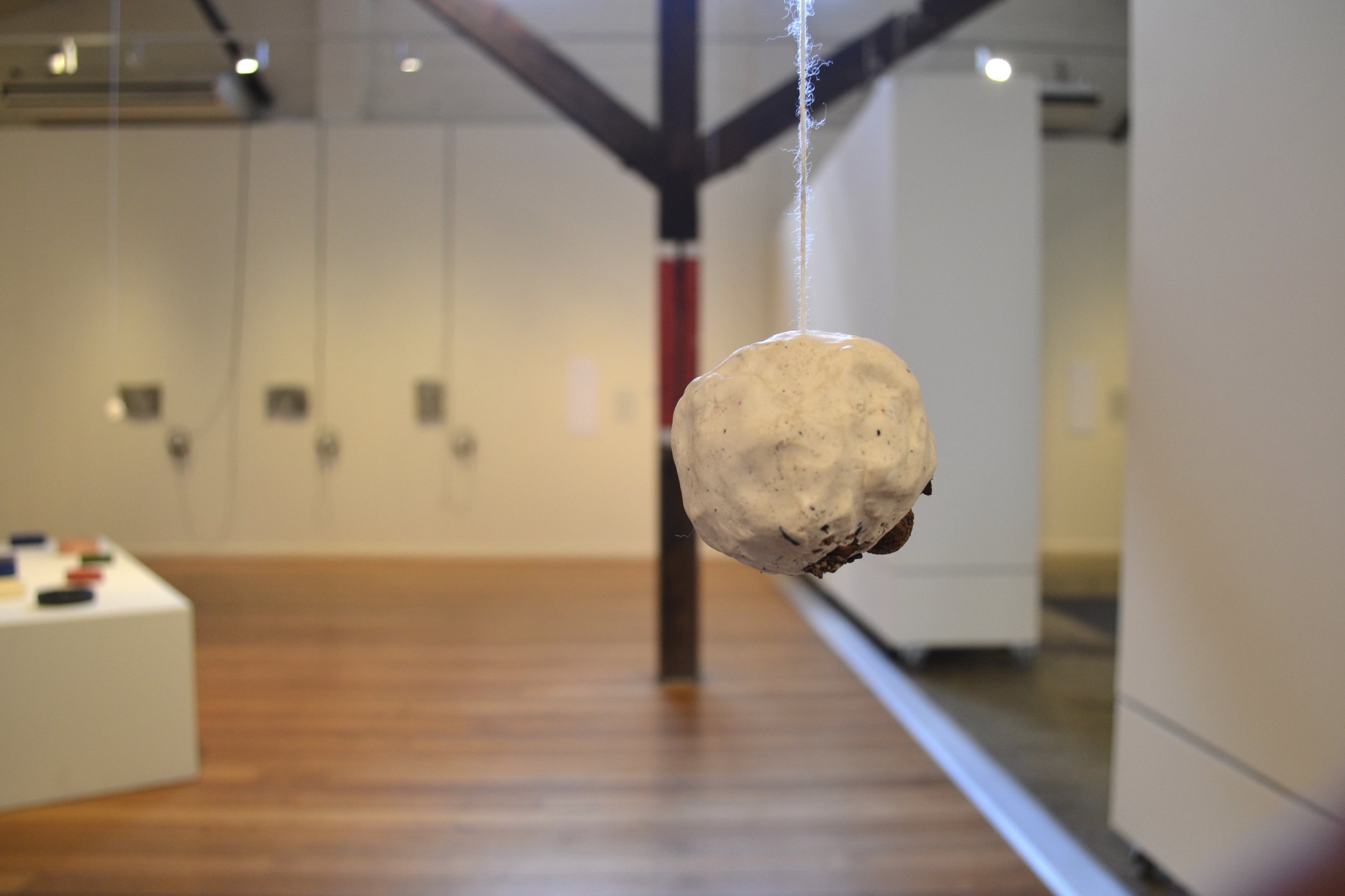

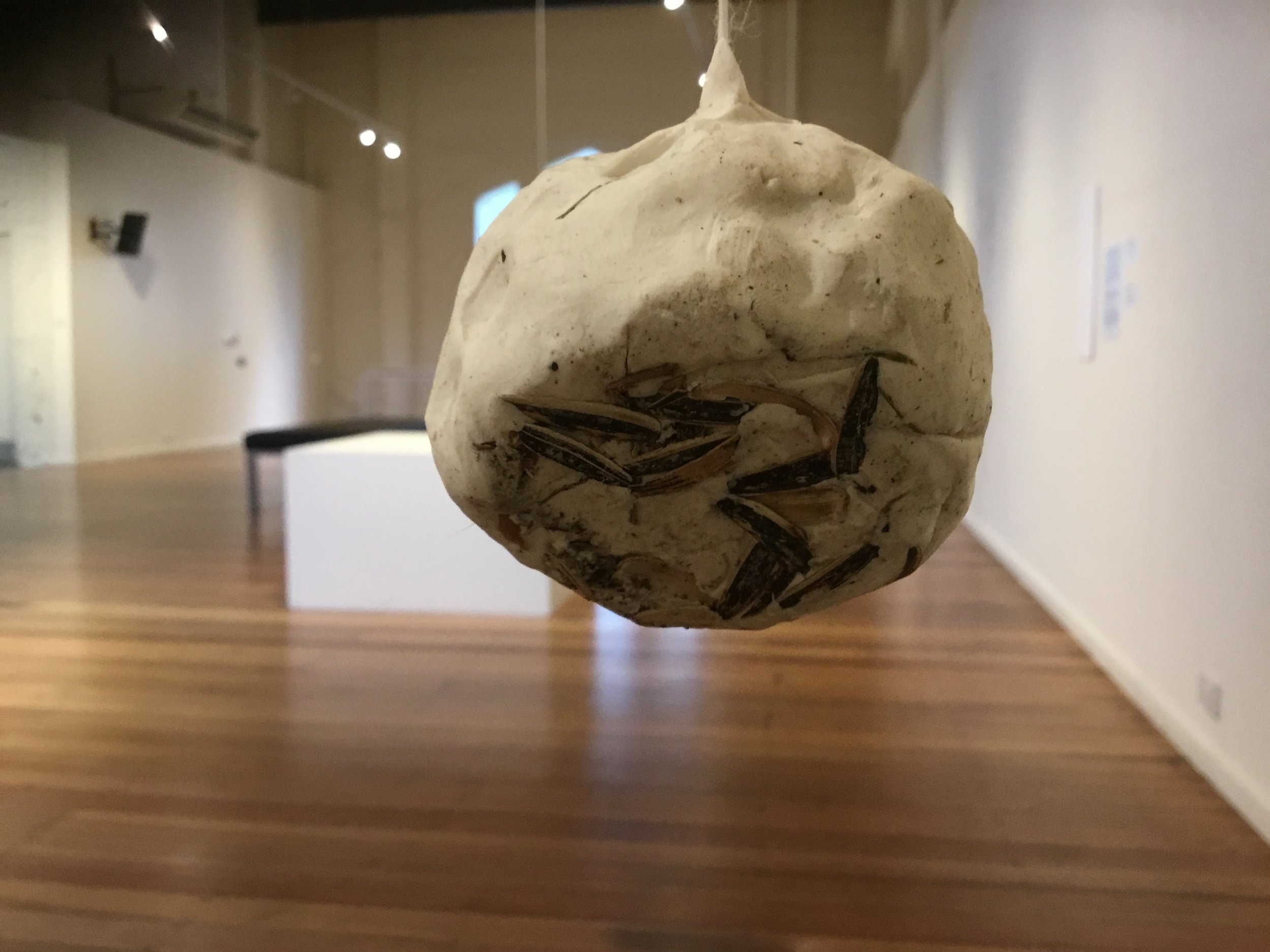

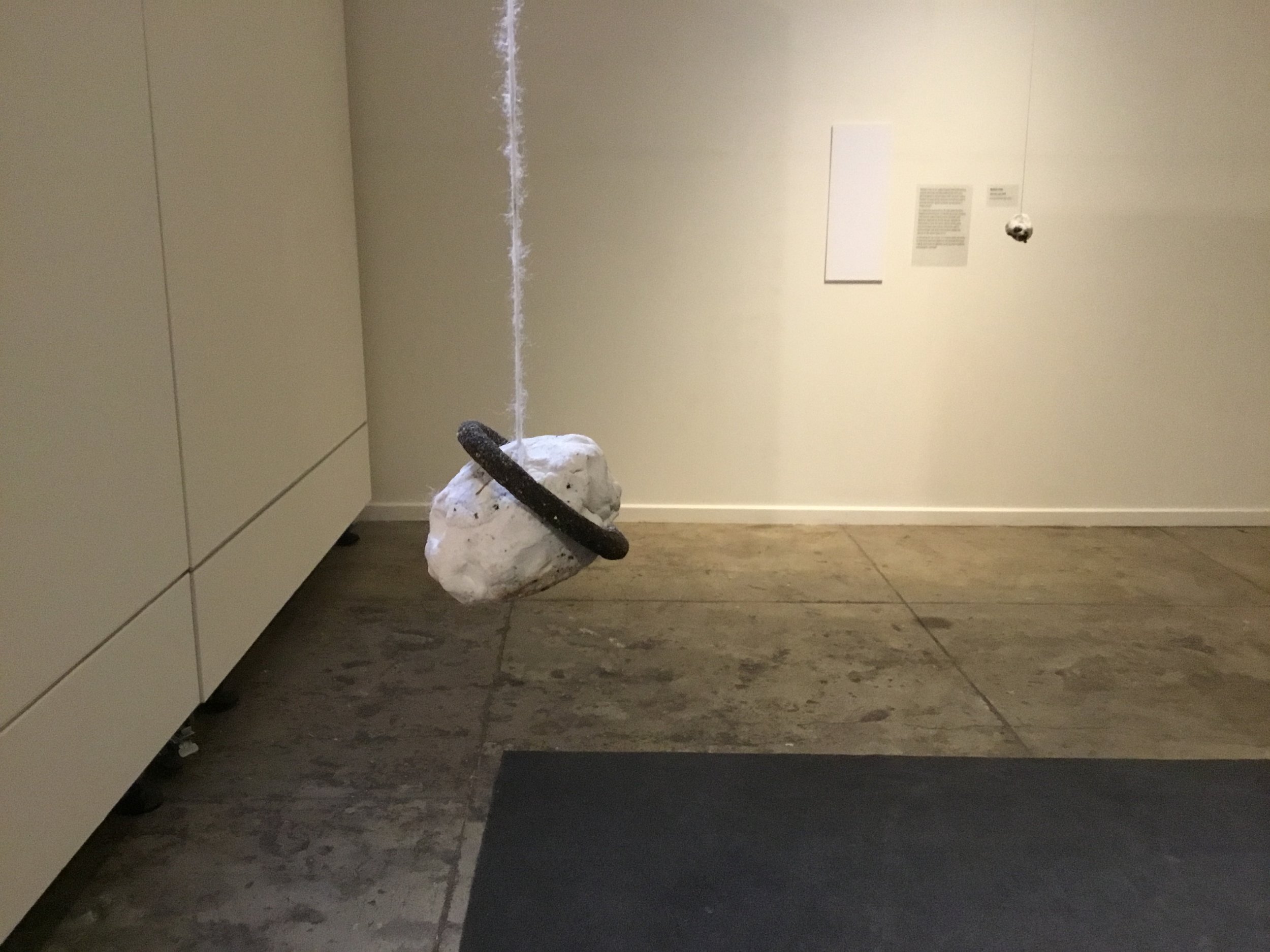

More Grey, plasticine, wool, dirt stuff, dimensions variable, 2018

With Seeing Hands - group show

Incinerator Gallery, Aberfeldie

I made plasticine into large balls and stuck it on some wool and then fishing-style stuck stuff to them from off the ground. Attempting to make my reach further.

Nearly every time I did it a passer by would stop and help me retrieve my plasticine. They must have wondered what on earth I was doing.

I didn't bother to give any explanation.

But then people got too much and started not letting me do it at all, so I had to employ a support worker to keep them away.

Carmen Papalia also had work in “With Seeing Hands”. Here is a conversation Carmen and I had a few years later, which was commissioned for the book “Let's Go Outside: Art in Public”.

A pdf version of our discussion is available here, or the transcript is below. You can buy the book here.

Can You Be Your Whole Self Without Compromise?: Public Life, Public Accessibility, Public Art and Disability Justice.

A Dialogue between Carmen Papalia and Sam Petersen

Carmen Papalia uses organising strategies and improvisation to address his access to public space, the art institution and visual culture. His work, which takes forms ranging from collaborative performance to public intervention, is a response to the barriers and biases of the medical model of disability. Sam Petersen is interested in identity and the space around it. Her work has been focused on access—and the lack of it—to places, people’s minds, and opportunities. This is an edited transcript of a conversation that took place in November 2020 over video chat from the artists’ respective homes in Vancouver and Melbourne.

Carmen: I got your talking points. There’s a lot to get into; I feel like we have some of the same concerns when it comes to accessibility.

Sam: Thanks to you, I’m now doing visual descriptions of my work and it’s a whole new dimension that I’m very excited about. I think I’m more of a writer than anything else and now I have more to write about. Would you like a visual description?

C: Yes, yes, awesome.

S: Yay. I have mousy brown hair, fair skin. I am wearing a green, black and white plaid shirt and a creamy T-shirt with a face-hugger on it and it’s holding up a sign which says, ‘Free mask’. I’m in a power wheelchair. Behind me there is blue-sci fi bunting on the wall.

C: I’m intrigued about the policy you are trying to advocate for so that folks who require care or need personal assistance can go to hospital during COVID with their assistants. It’s necessary advocacy. I don’t know if I shared much about my time in hospital, but I go two or three times a year with my blood condition. I have these really intense painful episodes that are completely debilitating and they can land me in the ICU. I went to the hospital just over a month ago. My wife had to drop me off because of COVID restrictions and I needed visual assistance. I also don’t trust healthcare professionals, so it was this intimidating situation where I just had to lend myself to other people’s care without even knowing them.

After I was released from the hospital, I was told that I was exposed to COVID in the Emergency Room, so I had to quarantine for two weeks when I came home from the hospital. Luckily, I didn’t have COVID. I’d probably not be around if I got COVID.

S: Same, I don’t trust healthcare professionals. They aren’t given enough time to fully evaluate the situation.

I was terrified at the thought that I could get COVID-19 and would automatically get sent to hospital because my support workers didn’t have the PPE to support me and I would have no contact with anyone that knew me. When you have a disability, you can be treated like nothing very fast.

The nurses are so busy and I require a long time for people to understand me. The nurses can get short with me and that can be impossible to deal with when I am sick. It gets to the point where I don’t call on them even though I need to.

Even with the hoist and full body sling they use at the hospital to move me in and out of my wheelchair, I have experienced in previous stays that no one really knows how to use it [the hoist] except me, which isn’t much help, and they just try to figure it out together. Last time my support worker had to tell them they hadn’t put the sling on correctly before they tried to hoist me. I have had them use a sling back to front and another time, the wrong kind of sling.

The people at the top assure me the nurses know how to use a hoist, but I have seen that they don’t.

This act of not believing me occurs too often. Nurses will tell me I look tired and put me to bed against my will at 5pm.

C: This relates to one of your points about being infantilised and also the patronising assistance that you get sometimes.

S: Definitely. Could you talk a bit more about coming up against this? Some people assume I can’t make my own decisions and look to others or make decisions for me or often ignore me. This infantilisation is huge. Even with people I know, there is this condescension which leaves me out of decision making.

C: This is very much a problem that comes out of the medical model of disability—the idea that people need to be restored or fixed. It comes from the fact that for so long, people with disabilities have not had autonomy; they have not had the ability to self-determine as a community or as a culture. People with disabilities do require care from the medical establishment, but they don’t have agency when they’re in the care of the medical establishment.

It’s intense. We have so many harmful ideas about disability in our culture. Some of them go back to the Bible, such as you’re disabled because you have demons or you’ve sinned, and that [idea] has to be eradicated. I think those harmful ideas are embedded in the medical system. It’s evident in these interactions, [in] the fact that when we seek care, it’s a one-way relationship. You’re supposed to be grateful for the care that you receive, even if it doesn’t work for you. And you’re not thought to have anything to offer in that interaction; you’re just supposed to be a recipient. I think an ideal caring relationship is a reciprocal exchange. That’s why I really appreciate care collectives and disabled folks supporting each other, mutual aid that grows out of the disability justice movement.

Disability justice involves building capacity for care within our communities, outside of institutions, outside of the government context, care that we lacke on account of governmental failure and medical ableism.

S: That’s what I see.

C: Especially in the mental health context, it’s definitely about control. The medical-industrial complex is a carceral system in many ways.

There are a lot of people doing advocacy about the intersections of prison abolition and disability justice. There’s a new disability justice organization called the Abolition and Disability Justice Coalition. They emerged in response to the pandemic and the movement for Black lives. This group is addressing the medical establishment as a system of control and comes out of the anti-psychiatry movement, what people call the ‘mad movement’.

For example, someone has to sign a paper in order for you to leave the hospital, right? You’re being held—sometimes you’re even being held in medical custody. There are situations where people are sedated and restrained against their will or don’t have an advocate and then are completely coerced into procedures that they don’t want, and that’s a form of abuse. It’s easy to see how these systems cause harm when you consider them in relation to the worlds we make for ourselves in community.

S: [When] I was in rehab, it was humiliating: I had to get clearance to go out on my own. A nurse said ‘be careful’ and they didn't understand why it was so upsetting.

Once, [when] I was about to have an operation, I moved on the operation table and all the nurses came and got on top of me to keep me still, like a boob blanket. They were scared I would fall off the table. One of them said, ‘we better hurry up and put her to sleep’. I was indicating for my speech device because I needed to tell them that I was in an uncomfortable position and wanted to move a little. They were told about my communication device, but they didn’t give it to me.

I felt so . . . I haven’t got the words. Devastated maybe, and so angry. Like heat all through my chest.

I can see how it happened—they have a chronic lack of time, but that doesn’t make it right. They haven’t got time for me. They are always assuming the worst of me and others, and therefore seeing the worst of us.

C: You mentioned the term ‘infantilised’. I really connected with that. This happens to me all the time: people will ask whomever I am with what I want instead of asking me. They won’t talk to me because I’m being guided by a friend. It’s like I can’t make a decision for myself. I think the reason for that has something to do with the fact that disabled people are still underrepresented in public life. You still don’t see too many disabled people out in public places, living full and interesting lives.

S: Yes, it’s a vicious circle. People don’t see us because so much is inaccessible and this in turn means they don’t think of us, so things are not made accessible to us. Poverty can be a really big access problem, because we don’t have access built into buildings laws. For example, many artists can’t afford a wheelchair-accessible space, but what is the point if a significant part of the community can’t attend? A local Melbourne gallery went from being a wheelchair-accessible gallery to a non-wheelchair-accessible gallery because they wanted to provide free rent to the artists. I peed on their doorstep in protest, but the fuckers liked it.

Poverty is a social construct just like disability is. I am so angry that we are sold this scarcity all the time.

C: There’s a real inequality: why do we as disabled people have such low employment numbers? Do we have accessible work options, do we have workplaces that can accommodate the rhythms of our bodies or our capacities as they change and evolve? Very few workplaces are accommodating.

In Canada, I think the numbers are something like around 50 per cent of disabled folks have employment and less than half of the people who have employment have full-time employment. It’s because we don’t live in a culture where our government meaningfully supports us. It comes down to what we prioritise in our culture. We live under capitalism and that’s what divides us.

If you think about ideas of productivity or what it means to contribute to one’s society, people with disabilities are completely written off, they’re often dismissed as people who are leaching on the system—taking resources instead of contributing. That’s what it’s reduced to. It would be different if we valued a basic level of social welfare, or we valued collectivism or collective health. Grassroots spaces that are dedicated to disability justice provide a context where care and support are prioritized and people can maintain their dignity.

It comes back to ableism. I learned about the social model of disability when I was a young college student, and the idea that we are disabled by external conditions resonated with me. Your body is different than other people’s bodies. You have pain—of course, those things are difficult—but the conditions that disable us are social, cultural and political.

[We need] a culture shift around ableism—ableist premises, ableist practices in health care and the cultural secctor—we need to embrace different ways of being in the world, not just different ways of learning and participating in the spaces meant for us. Can you be your whole self without compromise? For most people who are disabled, that’s a ‘no’ in most situations, unless you’re around people that you can trust.

S: I didn’t learn about ableism until I was thirty-five. Like I could see it, but I didn’t know it had a name. I went to uni but the books were so inaccessible to me.

There was student help, but they often didn’t have good reading voices, or had a heavy accent, that made it hard for me to understand.

Yeah, people are so tired. Even me, I’m so tired of everything, so much ableism. I can only give out so much and the world doesn’t listen.

C: Yeah, I feel that. That’s why I’m an artist. It’s the way that I can shift thinking and it gives me the ability to have agency. I get to propose the kind of world that I want to live in through my work, or make space for the critique that I want us to make more space for. I can advocate in the art context in ways that might influence the wider culture or even policy in some cases. Only as an artist can I replace my cane with a marching band and use that band to navigate the city. [For the public artwork Mobility Device, 2013, Carmen has collaborated with local marching bands in places such as Santa Ana, California and in New York for the High Line, to produce a site-responsive score that uses musical cues to direct Carmen’s movements as he explores unfamiliar surrounds. The work creates an alternative and idiosyncratically sonic guiding system to his detection cane.] I want to live in that world, and I think that we really can through creative practice.

What is our position as disabled people in the wider culture; how do we interact with non-disabled people? It’s usually in these very limited ways where people are trying to take care of us—it’s not in a way that supports our autonomy. As an artist who makes work for public spaces, I can pose a vision for a future or a world that I want to live in where I don’t prescribe to those ableist values of my body or my capacity or my productivity or whatever.

Art and creative practice offer so much possibility for us to radically re-envision what a museum could be or what it means to participate in one’s community. What care could look like if it was more personal.

I don’t know what I’d do if I didn’t have art. I’ve been in dark places feeling completely limited in my ability to change things. I think this comes from my experience of being in hospital and being completely debilitated, and not able to advocate for myself when I’m having an episode, relying on people who are more bound to protocol than care. And that doesn’t always go well—the care.

It makes me worried that I don’t live in a culture that values my life. We still want to hide disability, but we need to use our presence and creative practice to center ourselves and disrupt public space. I think we do this anyway as disabled people. There’s this great example from the United States, [where] these activists with ADAPT were protesting the cuts to the Affordable Care Act as a lot of disabled folks were losing basic services that they relied on, like in-home care. Some of the activists were wheelchair users, and cops were trying to arrest them, but they couldn’t—they didn’t know what to do with their chairs. It was this interruption of the process of being arrested.

I think we as disabled people make roadblocks in many ways. When I’m ordering a coffee, I have to ask for extra help or, ‘What’s on the menu?’, etc., and people are frustrated standing behind me waiting in line. I’m taking forever. I think that’s a place of possibility—that’s why I made the work Long Cane, 2009. I created this absurdist 15 foot [4.5 metre] white mobility cane that I would go on walks with, and it would take the entire sidewalk up and people would have to jump out of my way. It’s like I’m inflicting disability on the wider culture.

I feel like people just have to deal with that discomfort. They have to deal with the messiness of the human body, the messiness of our experiences. That’s part of humanity. We need to be able to be sick and messy and human—part of being human is having a body that is different.

S: Somebody once said to me, ‘Why are you always stopping in the walkway?’ The amount of obstacles I have to get through all the time! I love your cane. The sheer audacity of it.

I once created a rainbow burn out [Rainbow Burnout, 2012]—red, yellow and blue chalk mixed with water. I went round and round, right in the middle of the footpath.

C: I think about disability as a culture. I rarely see my experience or the way I understand myself reflected back to me in public or at a museum, and I want to see that more. It’s important for us to occupy public platforms and start speaking for ourselves and defining the terms around our care and participation in these spaces, and not just as visitors. If you think about the ways museums have engaged people with disabilities from the time they were invited in, it was as a visitor. Accessibility programs in museums grew out of education programs, and it was a patronising model for participation that goes back to the ways we were engaged in medical settings. We were never the presenter or featured artist.

Some of my friends in the low-vision community have never been to an art museum or gallery because they feel like ‘Oh, that’s not for me’. A blind friend of mine who is a paralympic athlete was surprised when he asked what I was studying in grad school and I said art. These biases exist within the disability community. I think it’s due to a tradition of exclusion: we could never imagine ourselves as artists because that experience was not available to us.

S: I’m not very comfortable saying I’m an artist because people see that as childish. Often, I say it anyway because I’m trying to break down the stereotype, but it’s still there.

C: I hear this from some of my friends in the disability community who are artists as well. My friend in the UK who is a prominent disabled dancer and scholar told me about a doctor’s visit where her doctor asked, ‘What do you do for work?’ and she explained, ‘I’m a dancer’ and he replied, ‘Really? You’re a dancer?’ It’s bias and it’s a form of discrimination. It really limits your perception of self.

S: My work hasn’t always been accessible in other ways, like visually, and I’m not sure how to make my art more accessible to non-artists. Maybe that’s why I have been turning to spoken word. I can reach further into people’s minds with words, make them squirm. And these works can live on YouTube, making them truly public.

C: It isn’t your responsibility to make all your work accessible to everybody all the time. Some artists try to do that, but that’s extra labour on you, the artist, where you’re already concerned with your own access and trying to navigate the barriers that you encounter. It’s the responsibility of the institution that’s presenting the work to make it accessible to the publics they are catering to. Is it our responsibility, as disabled artists, to make our work accessible to the broader disability community? For me, I started making work in an effort to reach an uninformed, non-disabled audience. I wasn’t trying to speak to disabled people when I was making that long cane, I was trying to speak to non-disabled people. I didn’t initially think of disabled people as the audience for my work because I figured they already knew what I was trying to say.

When it comes to accessibility, the conditions and the people in the room are always changing—the biases that they bring with them, their politics, are always changing. So the culture of whatever space we’re talking about is always in flux. How can we ensure accessibility is available in all ways on an ongoing basis? I don’t think it is possible. I think accessibility is temporary. It’s something that has to be achieved collectively through an agreement with everybody in the room. I think of accessibility as a temporary, collectively held space.

In terms of the walking tours I lead [such as Blind Field Shuttle, 2010, a non-visual walking tour for groups of up to ninety people in which participants line up behind the artist, link arms, and agree to shut their eyes for an approximately one hour-long guided walk through cities or rural landscapes], people often ask, ‘How do you address accessibility since people who use wheelchairs can’t easily participate in that project?’ In response, I usually offer an alternative one-on-one experience with eyes closed. I’ve also modified it in various ways for different audiences. Sometimes I lead walks where it’s not everybody lining up behind me and linking arms with me leading at the front, but instead it’s me facilitating an experience in a wide open space where participants can shut their eyes and roam independently. I try to figure out what I am offering, and who I am offering it to, and make it available in different ways based on the situation.

S: I know it’s not my responsibility to make my work fully accessible, but I also think every iteration of the work is still the work, so I want a hand in that as much as I can.

My work is from the self, so I don’t feel it is to any particular audience, but it’s very angry and I don’t tend to show anger to anyone who has disabilities. So, I guess it’s for ables.

C: I have some questions for you, Sam, that I have posed to other disabled artists. Was there a place that you have worked or an experience that you have had as an artist that you would characterise as being accessible? Alternatively, was there a place or experience that was disabling?

S: My 2017 solo show at the old TCB Art Incorporated was located at an art space that was far from wheelchair accessible and didn’t address many other accessibilities. It had a few flights of rickety stairs with no rails and no lift. The exhibition I made was called I’m Not There Because I Couldn’t Be There.

C: I really like that. Not the lack of access, your title.

S: That was the reason I said ‘yes’ to having a show there—so I could make a statement about not being there. I had put plasticine on the back of blank canvases so that they couldn’t see it. It was amazing how many people still asked at the opening, ‘Where is Sam?’ [In the gallery’s Instagram posts about the exhibition, there were reminders that the gallery was not wheelchair accessible.] They simply could not see the lack of access. I had them sprinkle yellow glitter all over the floor of the gallery (wee representations). I like to think that it was the last straw. They had been there for years, and mine was the last exhibition they showed there.

C: That’s really funny and sad. It reminds me of an artist friend in New York, Shannon Finnegan. She was in a group show and the gallery was up a flight of stairs but there’s another space at the bottom of these stairs. To address the inaccessibility of the venue, she established what she called the ‘Anti-Stairs Club Lounge’ which was this space that you could only access if you signed an agreement and vowed not to ever step foot in the gallery. If you agreed not to use the stairs, you would be invited into this comfortable space that was more accessible from a disability perspective.

S: Awesome.

C: Yeah, she also did this at The Vessel in New York City. This newly built performance venue is not fully accessible. The city funded it and it’s supposed to be this exciting presentation space. Shannon hosted a protest there and had people sign declarations about not ever stepping foot into the venue as long as it was inaccessible.

S: Wow.

C: Another question: what actions are necessary in order to establish a context where the contributions of disabled artists/curators/creative practitioners can take root and thrive and become a vital part of the cultural ecology?

S: For people to slow down and respect everyone. I see that as the big thing stopping us.

C: Can someone who is disabled be separated from the effort to negotiate barriers in public life?

S: No, I can’t separate art and activism. More people need to start by giving up space, space that isn’t theirs to give.

C: I wonder if we can’t separate art and activism because as disabled people who are trying to be self-determined and autonomous as artists and to make a statement about the world we want to live in, we are politicised. Because we’re underrepresented, we don’t hold a position of privilege in our communities. My friend in Portland who is a disabled dancer has observed, ‘It shouldn’t be radical to be independent as a disabled person’, but that’s where we’re at because, given the circumstances, we are in survival mode most of the time.

Can you make art not about disability or your experience? I don’t know if I can. For me, that wouldn’t be interesting either because that would be a luxury. I don’t think I can spend my time not making work about disability, not doing advocacy or something that improves my life or experience.

S: Totally.

C: When you think about accessibility or mutual support in the communities that you belong to/serve, what comes to mind? What does accessibility mean in your community and how is it practiced?

S: I am not really part of anything. Maybe I will be but I’m not counting on it. Community is where you feel safe and accepted and I have never felt that. Many people let me down and that isn’t safe.

C: Do you have disability justice organisations or places that are radical, like grassroots disability-led spaces, in Australia? What’s the scene? The sense that I get from other people is that it is limited. I didn’t know about the disability arts movement until I met another disabled artist. I didn’t’ know there was a world out there of radical disabled folks who loved parts of their experience and wanted to share that with others and felt proud to be disabled. I think it’s internalised ableism that doesn’t allow us to love our experience. I love the perspective that I have and the way that I can navigate the world because I am disabled.

There’s even parts of my really severe pain condition that I love. It’s made me a really good advocate for myself and a problem-solver, and it’s brought me closer to other people. I make close relationships with people, I have to make relationships that are based on trust because I need their help, I need their support, and I need them to understand what I need when I’m in an emergency. I don’t know if I’d have that sense of myself or that perception of myself if I didn’t find other disabled people who were banding together and making art, posing these critiques and making space for these discussions.

You feel really alone sometimes, when you’re not aware that others are out there, or you forget that others are out there. At my most isolated moments, I think about the fact that people like you are out there doing your work and you care about these things too. We’re all contributing to parts of the same project. I need to stay connected to community to remember that there is progress. It’s a hard thing though because we are very much underrepresented in the arts, in public life, especially now with COVID. People are less outside in public now, especially people with vulnerable immune systems. I would die if I got COVID. I have had to really limit my interactions.

There really is power in numbers and there’s power in community, especially when it’s a disability-led space.

S: Totally. Yeah, it is the connection with others and the lack of it for so long. It can still be overwhelming.

C: Do you know the Disability Visibility Project? It’s a website and a podcast run by Alice Wong, an activist in California. It is such an affirming space for disability culture. When you’re on the site, as a screen reader, all the images are described and they’re described with care, and that nonvisual experience is really considered. Alice is bringing her own experience and her perspective of disability to the site, and it’s all content that is by and for disabled people and it’s beautiful. It’s a space where you can see the vibrancy of disability culture.

It makes such a difference when it’s a space that’s for and by disabled people. I think about stuff like disability on Twitter or disabled Twitter or whatever they call it, people make an effort to describe their images. They know who their audience is, it’s other disabled people. I like that effort and practice because that’s the kind of responsive, connected community that I want to be part of. For some of my disabled friends, these online spaces are some of the only places they can find connection with people like them.

S: Thank you, and there are some awesome people I know, it’s just hard for us to connect.

C: I feel the same way. Before COVID times, it was hard to connect too, just getting coordinated to meet another group. I like to make the joke: ‘How am I going to find another blind person anyway?’

S: Have things become more accessible for you during the pandemic?

C: Staying in touch with people has been easier. While it is just on Zoom, I’ve been talking to a lot of friends that way. In some ways it’s completely restrictive too, and I feel super vulnerable now in terms of my health and the places that I can go safely.

COVID has been super destabilising on a major scale for so many reasons, and there’s some potential there for things to change. I think when the world returns—I’ll just say ‘returns’ because I don’t like using the word ‘normal’—I think people are thinking about how can we do things better, how can we accommodate people better? At a large scale right now, people are having to navigate their own vulnerability when they’ve never really had to think about it before and to deal with inconveniences that are out of their control.

That’s the experience of being disabled: you’re in a constant state of vulnerability, there’s inconveniences, there’s barriers that you just have to put up with, there’s all these things out of your control. In some ways, it’s great practice for people in general to have that experience of not having things instantly accessible for them. I’ve seen it shift the way people talk to each other too, just in meetings and stuff with people asking, ‘How are you? How’s everyone feeling today?’ When did we even want to make space for the way people felt in a corporate setting before COVID? Now people are like, ‘How are you feeling?’ and people actually say that they’re depressed, they say that they’re feeling anxious, worried, they’ve had a death in the family.

There’s a reason for people to offer care more than they did before, and I think that’s a good thing. I read somewhere that times after pandemic have historically been times of social cohesion and that people are less likely to put up with inequality. It’s hard to be hopeful right now and I obviously feel super depressed with what’s going on over here. I heard in Melbourne there’s no cases right now and people are back to their routines in some way. In Canada, it’s pretty terrible. It’s hard to keep that hopefulness, but what makes me feel not completely crushed is that the pandemic has been a time of communities coming together to support each other with all the mutual aid efforts, the free meal programs, the free counselling services that are becoming immediately available.I feel very lucky to be working as an artist right now, and to be honest I have [had] more work and more support to do the work I do since the pandemic. And I’m able to work from home, which is amazing. A lot of museums right now are asking, ‘How do we do accessibility better?’ They’re actually asking the question, ‘How do we do this?’ and I feel like it’s time that we tell them exactly how to do it, and it’s not just about providing the basics or those conventional accessibility offerings or services. It’s about radically re-envisioning what it means to participate—so you can participate on your terms.

How do you change or re-envision systems and practices so they’re more supportive of the rhythm of the disabled body? What if a non-profit or a museum or a gallery or public art program or whatever was to, instead of trying to achieve growth on an ongoing basis, actually follow the rhythm of a disabled body and reassess what should be prioritised from season to season. For myself, my pain condition is triggered with changes in weather and barometric pressure. I work differently in the winter than I do in the summer. What if a gallery did the same thing? Maybe there’s times where it wouldn’t offer public programming because it needed to address its internal functions.

S: Totally. We used to live with the seasons. That slowing down doesn’t happen anymore.

Note: Sam Petersen would like to inform readers that since this interview was recorded, a new disability justice group, the Australian Disability Justice Network (DJN), has formed. DJN is ‘led by and for multiply-marginalised disabled people across so-called Australia’, comprising members who have come together ‘in the spirit of love and justice’ to ‘share space, organise, provide mutual aid, and care for each other’.

Charlotte Day, Callum Morton and Amy Spiers (eds), Let's Go Outside: Art in Public, Monash University Museum of Art, Monash Art Projects and Monash Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2022 (forthcoming).